I entered this class with a vague idea of what it would be teaching. Now that I’ve listened to introductions on its topics, I’m fairly confident this class will equip me with invaluable skills for today’s world. When I think of digital rhetoric, I think of the Internet’s writing. I think of websites, social media posts, articles, PDFs, and videos. I think of how the creators of this content take special care to visually present their message with the right fonts, formats, colors, and images. Then I think of how eager I am to apply these tools of digital rhetoric to my own media platforms.

Since the early summer of 2019, I’ve been investing my time and energy into building an author website and Instagram page. I primarily post on Instagram, but when I do post on the blog, I promote it on Instagram and include the link in my bio. I’ve worked hard to achieve a visually pleasing aesthetic while remaining true to my style and my goals with the platforms. Yet I hope to learn how to develop the best methods of communicating digitally so I might reach my target audience and accumulate followers and readers.

Above is home page for my author website and blog. Before even knowing what digital rhetoric really was, I tried to make my writing more accessible and noticeable by including links on the home page to two of the most recent posts. While I have yet to traditionally publish any short stories or novels, I have the heading Upcoming Projects under which I share what WIPs I’m working on. With this class, I will apply the tricks of digital rhetoric to boost this page’s appeal and design.

Above is the blog page, or landing page, of my website. There, all my posts are listed with tiny blurbs to strike interest and images that correspond with the pictures used in the post themselves. I took smart, digital writing tips from other websites and bloggers’ advice when creating this organized filing system for the posts. I also took tips from successful authors and included widgets in the right column of the page. There, readers see a couple of recent posts from my Instagram and can click on those images, which takes them straight to my Instagram profile. While I am pleased with the blog page’s design and format, I want to learn how to better write for the medium.

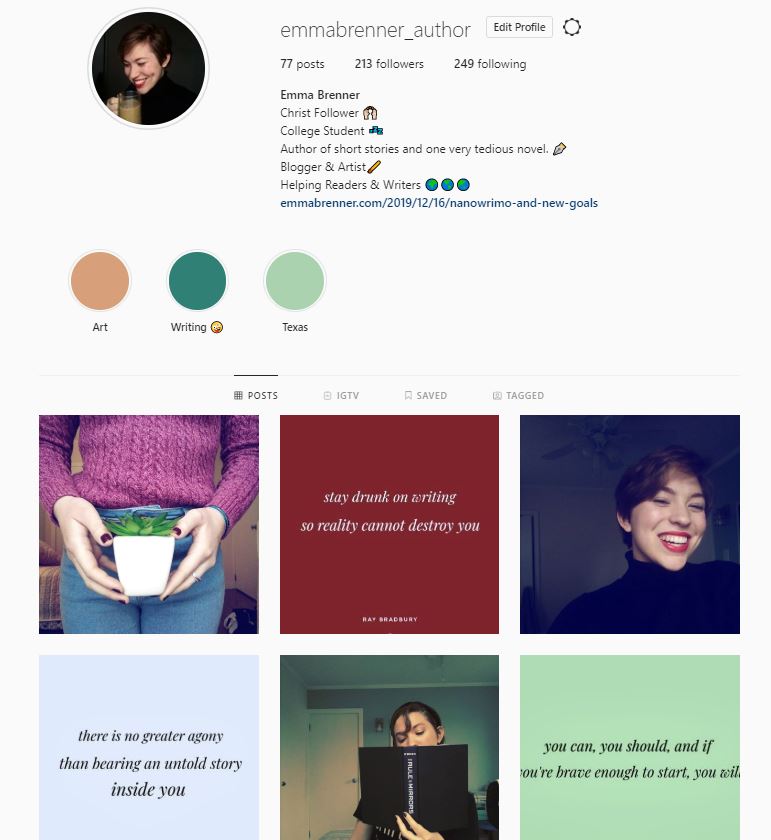

As for the Instagram page, I have recently applied many of the digital rhetoric tools and tips I’ve learned from observation and reading articles on social media success. It wasn’t until a month ago that I began establishing a color palette and aesthetic to my posts. With this change, I created a pattern for my feed, where there’s a quote on a color block for every other post to break up the images. While I like the design so far, and I feel it is clean and visually appealing, learning more of digital rhetoric will allow me to draw on whatever skills I have honed to make them even better. Like with the website, it will educate me on how to write, post, photograph, and tag better for my audience’s tastes.

I am happy with what I’ve accomplished. But I believe digital rhetoric can help me do more.

With this digital rhetoric class, I intend to apply its tools and methods in order to improve these media platforms. I hope to further understand the value of hashtags and to use them in the right places at the right times. I want to understand my audience in a deeper way and learn how to connect with them. I am certain digital rhetoric and its lectures on how to write successfully on digital canvasses will help me achieve this.